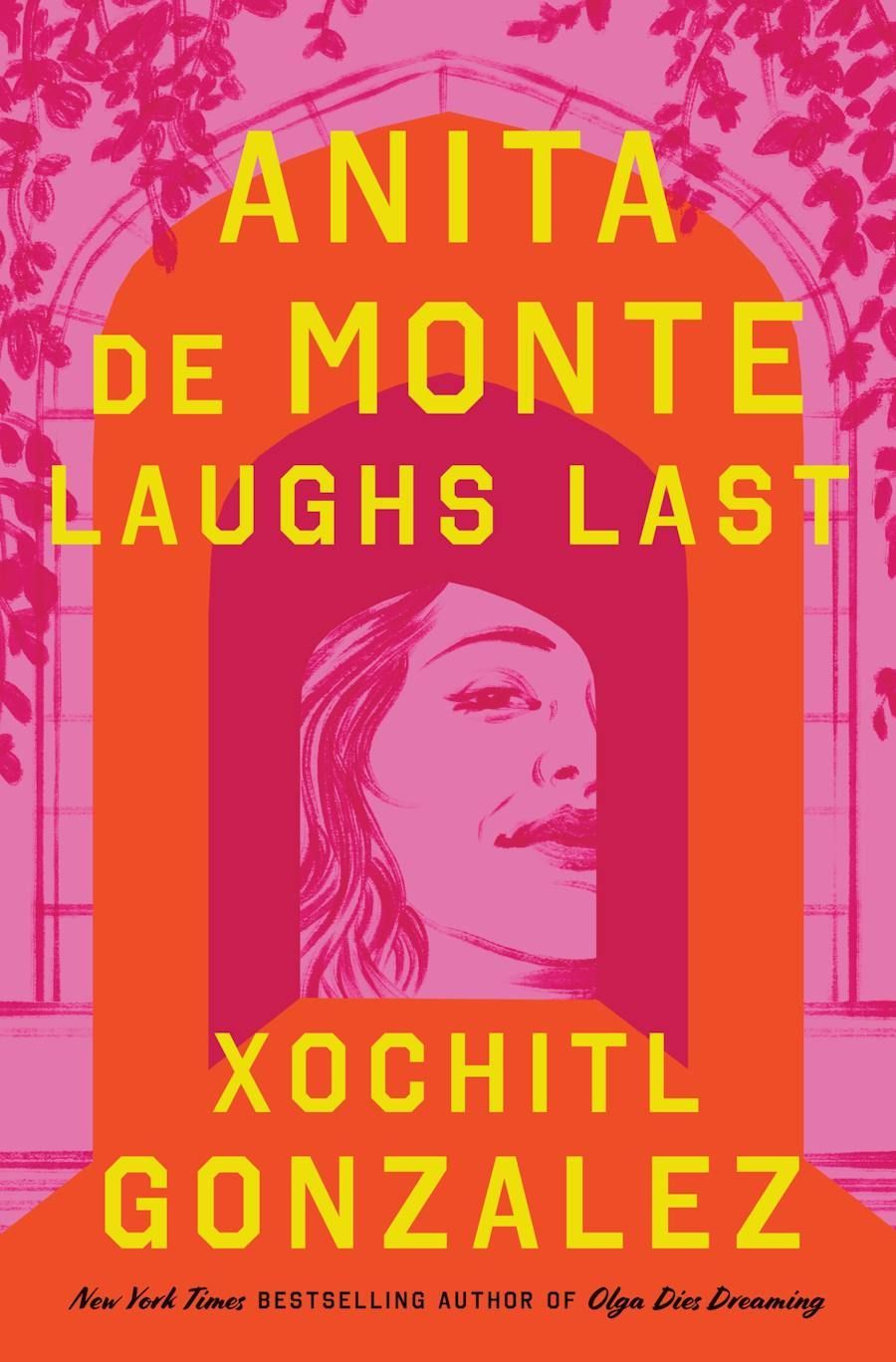

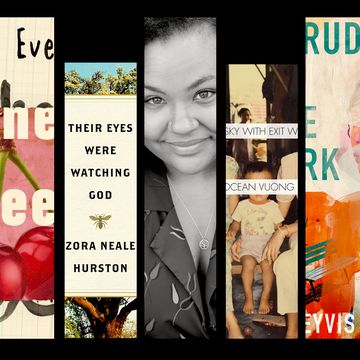

Anita de Monte, like so much good art before her, was born of recognition. Xochitl Gonzalez, author of 2022’s Olga Dies Dreaming and a staff writer at The Atlantic, discovered Anita camped out in her own memories, ripened in the heat of an Iowan summer in 2020. Gonzalez had already sold Olga to a publisher; she’d concurrently sold the adaptation rights to Hulu, and was writing and co-producing a series starring Aubrey Plaza in the titular role. But this was Hollywood: The work was overburdened with stops-and-starts, and Gonzalez could feel the whole thing slipping outside her grasp. After one particular call with a co-producer to discuss show notes, she ventured outside her home at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in Iowa City, and found herself reflecting on the art history course she’d studied at Brown University.

“The process of trying to make television ... It made me think about how difficult it was for Latino creators, Latinas in particular,” Gonzalez tells me when we meet over Zoom in February. “I found myself remembering my art history class, where I never saw anybody like me in class for four years. And I found myself remembering Ana Mendieta’s story.”

Ana Mendieta is not Anita de Monte, though Gonzalez is transparent about the borrowed biographical details. In 1985, the 36-year-old Cuban artist Mendieta plummeted from the window of her 34th-floor apartment; her husband, the minimalist artist Carl Andre, was charged with her murder, sending the art world into chaos. Later, a judge would rule Andre not guilty, but many of Mendieta’s fans and family members continued to protest his acquittal and protect her legacy. Thinking of Mendieta’s story decades later, Gonzalez rushed home and poured its basic facts into the vessel of a character, a woman named Anita de Monte. She, too, would be a Cuban artist, one who’d marry a famous minimalist—this time named Jack Martin—and later fall from their apartment window. The story started as the outline of a script; later, the author would transform it into a novel.

A day after Olga hit the bestseller list, Gonzalez learned Hulu was passing on the television adaptation. As she toured the country promoting Olga, she quietly funneled her feelings of disappointment and dismissal into the fiery avatar of Anita. “Obviously the story is inspired by Ana Mendieta,” Gonzalez says. “But, really, what ended up happening was ... this sense of feeling like you can’t get forward. And that people aren’t understanding what you’re trying to do. [Anita] sort of became the story, which is an homage to this thing that happened to this really talented woman. But the character, Anita, ended up being all of my own frustration with this process.”

The resulting novel is a triumph, a fascinating interplay of biographical reality and invention, magical realism and historical homage. The chapters alternate across two timelines, one in the ’80s, focusing on Anita and Jack, and another in the ’90s, following Brown art history student Raquel Toro, whose relationship with a wealthy white student mirrors Anita’s own tumultuous romance with Jack.

Originally titled Legacies in its work-in-progress form, Anita de Monte Laughs Last concerns itself not only with the autonomy of Anita herself (and, by extension, Mendieta), but with the larger art world’s clouded perspective about who and what deserves recognition amongst the masterpieces. As such, the book opens with a jarring epigraph from the preface of Gonzalez’s own art history textbook. Written by Anthony F. Janson for the 1994 edition of History of Art, Volume II, and used in Gonzalez’ time at Brown, it reads: “Why, indeed, should one not include artists who embody very different sensibilities from that of the European and the mainstream? There is, in principle, no reason to exclude them whatsoever. However, I have decided to limit this edition to Western art ... I have taken a stand about what art I think is most significant that not all readers will agree with, since it favors universality over ethnocentricity.”

Anita targets the brutal dismissal at the core of this sentiment, and in doing so gives the women it involves—Anita, Raquel, Mendieta, Gonzalez—a voice with which to condemn it. Both Anita and Mendieta earn a voice beyond the grave, while Raquel and Gonzalez are gifted the space with which to combat further violence.

Ahead, Gonzalez walks ELLE.com through the background that led her to both Mendieta and Anita, and how she makes room for their stories in her life.

After its screenplay-outline iteration, what did the first version of this book as a novel look like?

The first draft was really sad, actually. And it was all in third person, and I was revisiting college stuff, and that was so weird. My best friend read it, and she was like, “This book is too sad. There’s no humor here.” And I was talking to my friend, Felicita, who’s an artist, and she was like, “You need to go to Rome because [Mendieta] won the Rome Prize, and I feel like her spirit convenes in Rome.” So I literally went to the American Academy of Rome and sat in this grove of trees, and then it hit me that I needed to revise [Anita’s chapters] into first person. So I went back and I redid everything with her in first person, and then it found life.

I thought that it was liberating—and again, in some spiritual sense, Ana Mendieta was the basis, and you can do something in fiction that you can’t do in real life, which is give somebody agency after death.

I want to get a better idea of your own background in art history. Where did that fascination first begin?

People that know me well know that I’m obsessed with my high school [Edward R. Murrow High School in Brooklyn, New York]. I am one of the few people that was not traumatized by high school at all. I had this awesome teacher, Sheila Hanley, and she taught AP European History, and she would do one day a week where she did art history. And she’d find art related to whatever the thing was that we were doing.

So then when I got to Brown, to be honest, I was really struggling. The transition from New York City public school to elite private college was not smooth at all. I was drowning in the sociology class, and I was like, I’m going to take an art history class because I know that I like it. And I know that it makes sense. And then I ended up really loving it. Because of the open curriculum at Brown, I ended up being a visual art and art history major. The epigraph for the book was from my college textbook from my first survey class.

That epigraph is so good. It captures the very essence of the book.

Right. And the textbook’s not called History of Western Art, by the way, the book is called History of Art. I think I’d always been a really good student, and I’d always just been like, Well, they’re teaching me what’s important. When you’re young and the teacher’s in front of the classroom, unless your parents are ingraining in your head, “Question everything,” then you’re like, Well, this is what’s important. Which then means everything else either doesn’t exist or is not important.

I was known in the minority community as the art girl. That was my thing. So one of my friends in my senior year got me this book on Caribbean art, and it was actually quite academic. It had Mendieta. And I was wandering around, now my mind’s blown open. She’s sort of a totem for a lot of Latino women that are artsy. And now for a lot more women, her story is growing in popularity. I had this notion of: What would’ve happened had [Mendieta’s story] come to me while I still had the tools of school? I think what I see in Raquel’s journey is that she graduates with such confidence. She doesn’t have to stay in that world. But she walked straight into it. In some funny way, I think [her story] is almost more of an alternative history [of mine].

So you’d studied art history, discovered Mendieta’s story, but how did you eventually find your way to creative writing?

I got [to Brown] and I was like, “Oh, I’m going to take some creative writing classes at Brown.” Because I had written—we did this wacky thing at my high school called “Sing.” We would write an allegorical musical that was 45 minutes long, and you had to use pop tunes and change all the lyrics. I co-wrote the script every year that I was there. So I had written scripts and a little one-act play, and I wrote stories. So I was like, I’m going to try and do this [in college]. And then I got there my freshman year, and my roommate had won the Seventeen magazine fiction-writing contest and gone to Brown. [Laughs.] At 18, you’re just like, “Well, then I give up.”

So, anyway, I ended up going into the arts in a different way.

When did you land at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop?

That was almost five years ago that I went to Iowa, which is wild.

So when in that time did you reconnect with the story of Ana Mendieta? How did she eventually shape Anita de Monte?

I think I felt really reconnected to [Mendieta] when I got to Iowa, because she had come on Peter Pan and was sent to Iowa to a foster family, and then an orphanage. My first year I had done the outline [of what would become Anita de Monte]. I lived pretty close to the Iowa River, so I would go by the river because she’d done a lot of the pieces there. In the beginning it was like, Oh my God, it’s so weird that this is how I ended up coming back to art. And that it somehow involved Iowa.

My second year, after I’d done the outline, I hadn’t started writing the book. I didn’t know it was going to be my book. I taught, and I had two Latino kids in my class that were from Iowa, and they told me some stories that were pretty bad about racism they’d experienced, and... I imagined [Mendieta] really [young].

There’s this idea of the eager immigrant that is so wanting to be a part of America and not doing “it” good enough. And I was attracted to this idea that this poor girl didn’t want to come here. It was part of a political thing. And then suddenly she’s thrust into the heart of America at a time that was so different from now. I felt a real importance, a kinship to that sort of story.

So I talked to a lawyer, and I was like, “How close to the line can I get about the facts of this case?” I think I wanted to use the facts because some of them were just biographically attractive to me. Then once I went into it, it’s like, How can I give her the agency that the news doesn’t allow you to have? Which is to say, “Yeah, this is how he fucking threw me out a window.” I just was like, well, now I’m making a character. And these are my experiences of Iowa. This is my experience of being frustrated as an artist. This is my experience of why I make art.

I went to visit a high school, and they were like, “[Olga Dies Dreaming] is autofiction.” I was like, it is not autofiction. [Anita de Monte] isn’t autofiction either, by any means, but I am a kernel of both girls. This book feels way more personal.

You mentioned earlier why you switched Anita’s chapters from third-person perspective to first-person. But perhaps an equally fascinating decision was your choice to include whole chapters focusing on Jack’s perspective. Why?

It felt to me, even though obviously Anita’s the victim of a lot of abuse and of a crime, that she was in a toxic relationship that works on both sides. And I think it was important to give some insight into how it feels on the other side, and how that feeling causes action, right?

I’m actually kind of fascinated by middle-aged guys. There’s so few outlets for insecurity. And there’s so few outlets for validation. As much as Jack is the system, he feels like a bit of a charlatan himself, and that root insecurity is the source of so many problems in this book, and in the world to some extent. I thought that was important to show. It’s not a justification, but it felt important to walk through it.

I think when we think of jealousy in a relationship, we think of, “Don’t look at that man.” But actually, professional jealousy ... now my poor ex-husband’s getting dragged into this. But I remember one night—my poor ex-husband was very, very shy—and we went to a party and I was sick, and he was so charming. In the car ride back, I was like, “You were on a 10 tonight.” And he was like, “Well, if you dial it back to a seven, I have room to bring it up to a five.” I was like, “Okay, so I have to be sick for you to be fun.” [Professional jealousy], for me, was far more common.

You’ve lived a lot of lives, inhabited a number of industries, but now most of your work involves some type of writing: fiction, journalism for The Atlantic, screenwriting. How do you split up your writing time so all this creative work gets its designated space?

Most of the time, I don’t think of writing as heavy labor. So I’ll say I work every day in some capacity. It’s very rare I take a day off, but that might mean that I’m reading a book. I am very comfortable with not working on my novels every day. I don’t need to. And not only that, I don’t like to. I really prefer to get out of the city and go someplace for a month [to write novels]. And, ideally, it’s someplace close and people can come and visit.

Then I see the rest of the time being dedicated to my other two things [journalism and screenwriting]. Book promotion is kind of an added job responsibility. I look at the year. I’ve already blocked out my months when I’m away to work on my book. The summer is all my new book, and I’m really excited. But I don’t feel the pressure to have to pick it up every day.

I call it country work and city work. Journalism and scripts are city work, but for me, the novels are country work. I have to be able to imagine myself in these other places, so I need to be able to get in that space.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.