In the early 19th Century, it was fashionable for Europeans to collect wild animals from around the globe, bring them home and put them on display. One French dealer went further, bringing back the body of an adult African man. Dutch writer Frank Westerman came across the exhibit in a Spanish museum 30 years ago, and was determined to trace the man’s history.

His name is not known, only his nickname: El Negro.

His fame comes from his posthumous travels – lasting 170 years – from Botswana to a museum exhibition in France and Spain. Generations of Europeans gaped at his half-naked body, which had been stuffed and mounted by a taxidermist. There he stood, nameless, exhibited like a trophy.

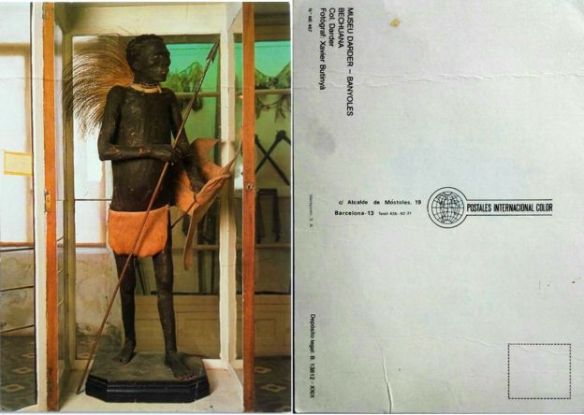

In the Darder Museum of Natural History in Banyoles, Spain, El Negro was prominently still on display in the 1980s. In the museum, “El Negro” was displayed standing in a glass case in the middle of the carpet.

postcard of “El Negro” on display in a Spanish museum

As Westerman states, “This was not Madame Tussaud’s. I was not staring at an illusion of authenticity – this black man was neither a cast nor some kind of mummy. He was a human being, displayed like yet another wildlife specimen. History dictated that the taxidermist was a white European and his object a black African.”

The story begins with Jules Verreaux, a French dealer in “naturalia”, who in 1831 witnessed the burial of a Tswana man in present-day Botswana. He returned at night to dig up the body and steal the skin, the skull and a few bones.

With the help of metal wire acting as a spine, wooden boards as shoulder blades, and stuffed with newspapers, Verreaux prepared and preserved the stolen body parts. Then he shipped him to Paris, along with a batch of stuffed animals in crates.

According to the French newspaper Le Constitutionnel, which was writing a review of “El Negro” on public display in France, the “individual of the Bechuana people” attracted more attention than the giraffes, hyenas or ostriches.

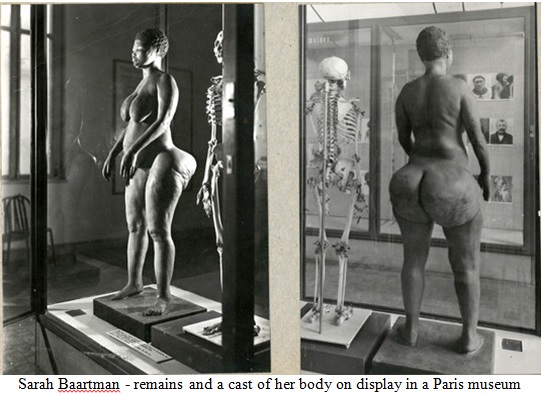

This disturbing scene is similar to that of Sarah Baartman. Baartman was a young Khoisan woman cajoled into going to Europe in 1810 to publicly exhibit her body, which Europeans viewed as unique and exotic. Stage-named the “Hottentot Venus”, she was paraded around “freak shows” in London and Paris, with crowds invited to look at her large buttocks. She eventually came to the attention of scientists who wanted to study her.

Even after she died, her brain, skeleton and sexual organs remained on display in a Paris museum until 1974. Her remains weren’t repatriated and buried in South Africa until 2002.

Another similarity is what the Germans did with skulls of indigenous populations in their colonies in present-day Namibia.

In German concentration camps, female Herero and Nama prisoners were forced to boil the severed heads of their own people. The skulls of the dead Herero and Nama were then placed in crates and shipped to museums, collections, and universities in Germany.

This practice was started by Eugen Fischer, a prominent German anthropologist, who first went to Namibia in 1904 wanting evidence to show that racial degeneration was real.

German South West Africa became a field laboratory of German racial scientists in the early 1900s, led by Fischer.

As late as 2008, Freiburg University still had 12 skulls from Namibia, and the Medical History Museum of Berlin’s Charitie Hospital had 47 Namibian skulls.

In October 2008, the Namibian government formally requested the repatriation of all Namibian remains still held in German universities. These skulls, eventually sent back to Namibia, received a proper burial in the land of their birth, and finally, the chance to rest in peace and dignity.

For “El Negro,” more than a century after his original display he was still in a Spanish museum.

Everything began to shift in 1992 when there were increasing calls El Negro should be removed from the museum. The Olympic Games were coming to Barcelona that year and the lake of Banyoles was the venue for the rowing competitions. Surely, any athletes and spectators who visited the local museum would take offense at the sight of a stuffed black man.

These calls were supported by prominent figures such as the US pastor Jesse Jackson and basketball player Magic Johnson. Kofi Annan, then still Assistant Secretary-General of the UN, condemned the exhibit as “repulsive” and “barbarically insensitive”.

But due to heavy resistance among the Catalan people, who embraced El Negro as a “national” treasure, it was not until March 1997 that El Negro disappeared from public view and was put into storage. Three years later, in 2000, he began his final journey home.

Spain had agreed to repatriate the human remains to Botswana for a ceremonial reburial.

The remains of the Tswana man lay in state for a day in the capital Gaborone, where an estimated 10,000 people walked past to pay their last respects, before he was laid to rest.

The story of “El Negro,” as well as that of Sarah Baartman and countless others, are representatives of the darkest aspects of Europe’s colonial past. They represented theories of “scientific racism” – the classification of people according to their supposed inferiority or superiority on the basis of skull measurements and other false assumptions

Today they are seen by many as the epitome of colonial exploitation and racism, of the ridicule and commodification of black people.

Pingback: Lovecraft Country – Queer, Black & Gifted